Doomsday mood in Yerevan? Oh no!

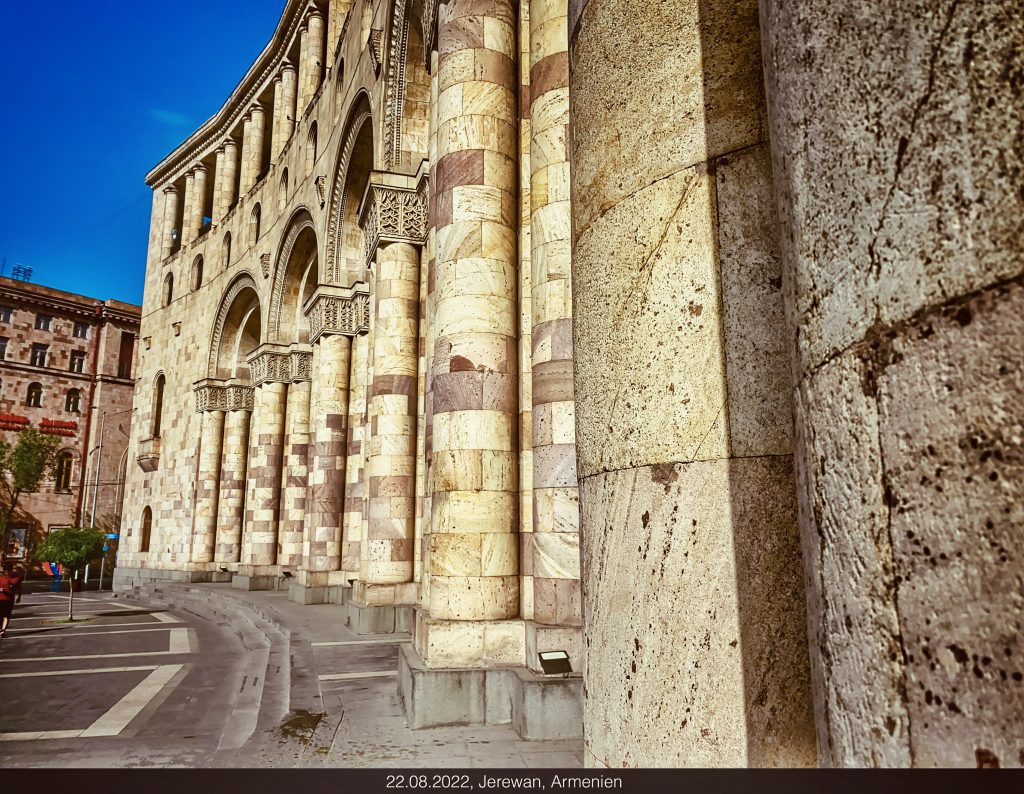

The wind of capitalism is blowing in Yerevan’s streets. Who is investing in the large hotel and residential complexes, the gigantic shopping malls and huge sports and event buildings here is beyond me. But, they are gigantic complexes and not always architecturally successful.

While we wait for our visa for Iran, we move from district to district and have finally arrived in one of these Soviet-era apartment complexes.

Dark corridors, no air conditioning, no lift. Instead, beautiful wooden floors, bright flats with high ceilings and green shade trees in front of the windows. It is our most beautiful, honest accommodation in this city. Airbnb as it was meant to be. A young woman who works abroad every now and then for longer periods of time rents out her flat during that time.

It’s hard to believe from the outside, but we feel really comfortable here and the time until we get our visa doesn’t seem so long. We live a little in this city.

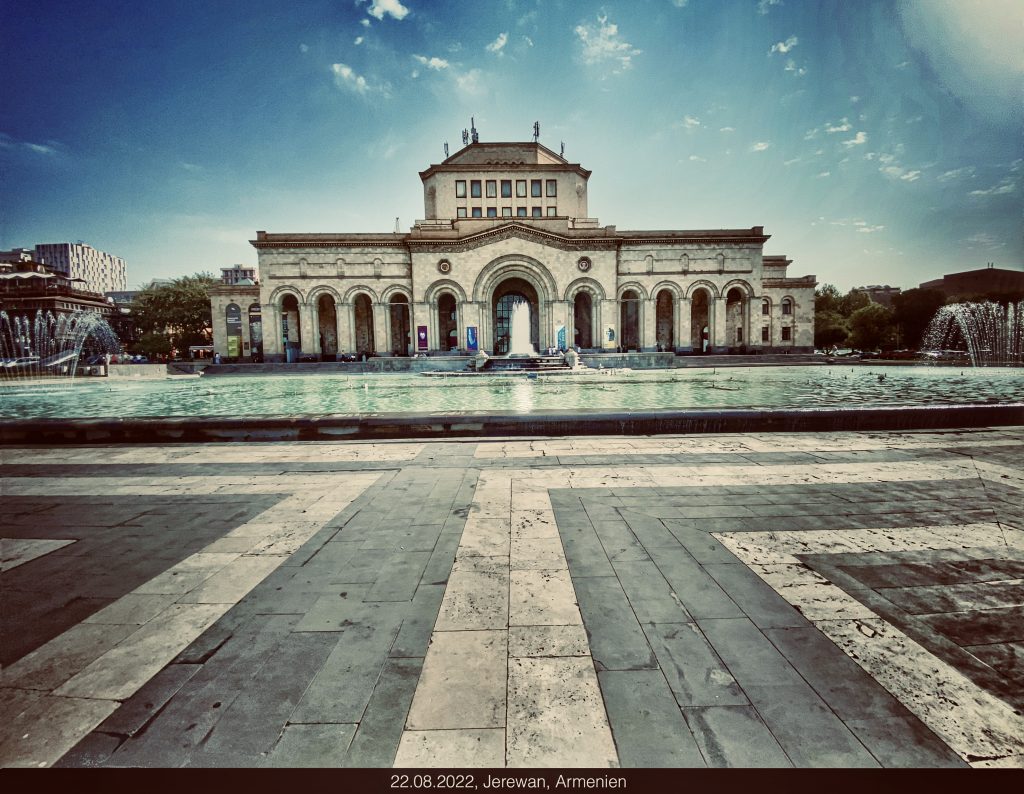

We explore Yerevan on foot, take the bicycles or the metro and slowly get a map of the city into our heads!

During my city tours in Berlin, I always see how people smile about soviet buildings and how my guests think prefabricated concrete slab buildings are the greatest evil in the world, how Brutalist architecture is misunderstood but Bauhaus immediately gets full recognition.

It was different before. Bauhaus was considered absurd. The magnificent buildings on Karl-Marx Allee were admired and envied by the West Germans, and how about Brutalism?

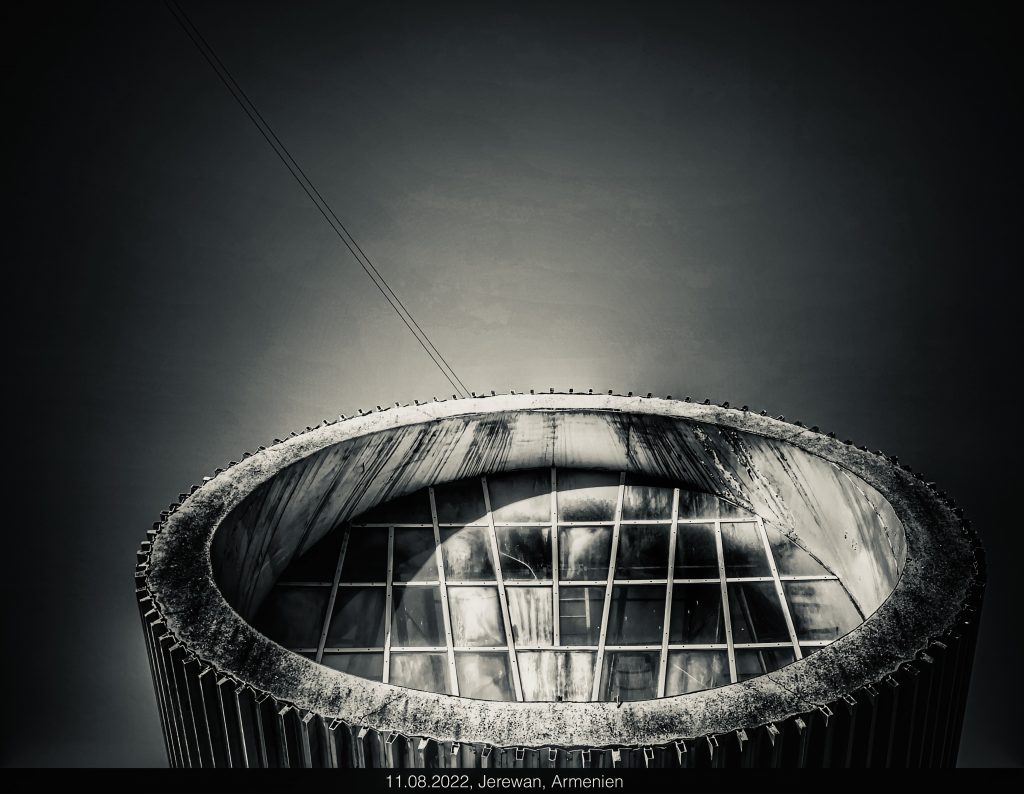

Raw, not brutal!

Actually, it should be called “brutism”, which has nothing to do with the term “brutal” as we know it. “Brutalism” derives from the French “béton brut”, “exposed concrete”. Le Corbusier, co-founder of modernist architecture, coined the term when he discovered the aesthetic fascination of raw concrete as a finishing touch for his buildings.

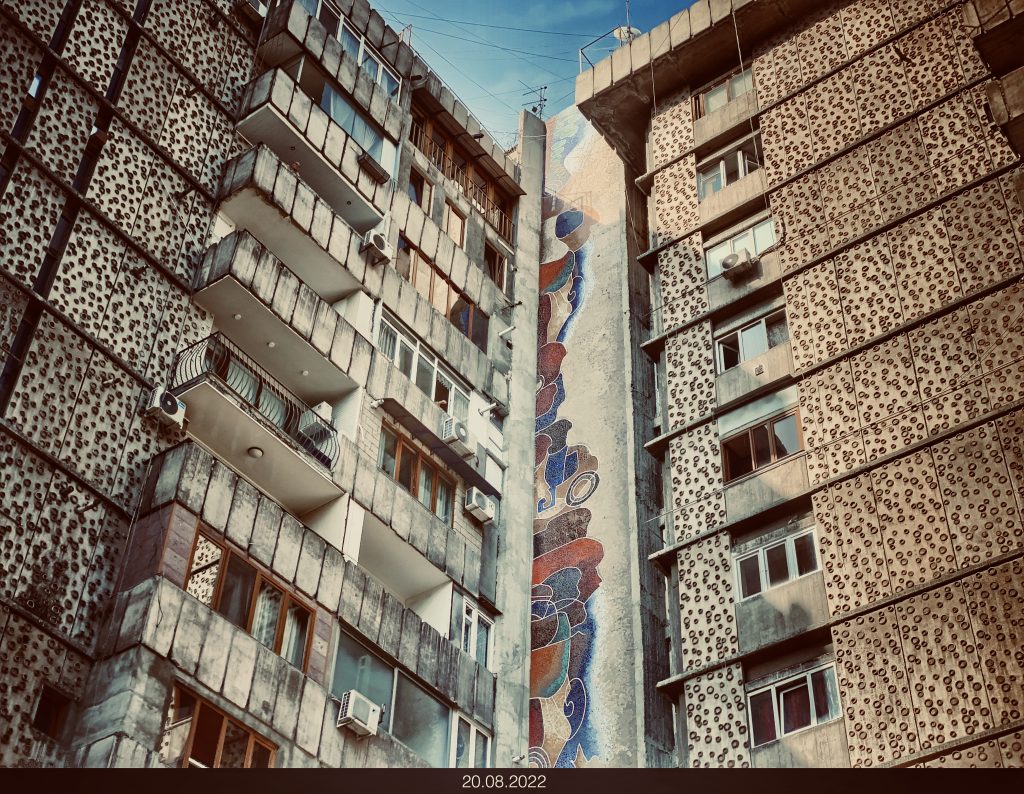

We also set out in Yerevan in search of such buildings in the style of Brutalism. And we found some great examples build during the Soviet-era.

And how about prefabricated concrete slab buildings?

“Perhaps it’s less about aesthetics and more about their historical significance“

Whoever, if you got such a flat in concrete slab building in Berlin in the 60s or 70s, whether in the West or East, you finally had central heating, your own bathroom, a room for you child. No more running water from the walls like in the Gründerzeit houses in Prenzlauer Berg. Which, just by the way, were the prefabricated buildings before the prefabricated building. One building just like the other. If you know one flat in this Gründerzeit houses, you know the others.

So the first attempts at serial building already existed at the beginning of the 20th century. And the reasons for it were the same from the beginning as they are today. It was necessary to house an increasing number of people in large cities, and preferably quickly and cheaply. With industrially produced concrete, a new building technique came along at just the right time. Ever-similar building components could be prefabricated in factories, regardless any weather conditions.

I think it is not true that there is nothing individual like it is often said . So many incredibly different people can live in these houses. It depends on them how diversely the living space is used.

And here in Yerevan?

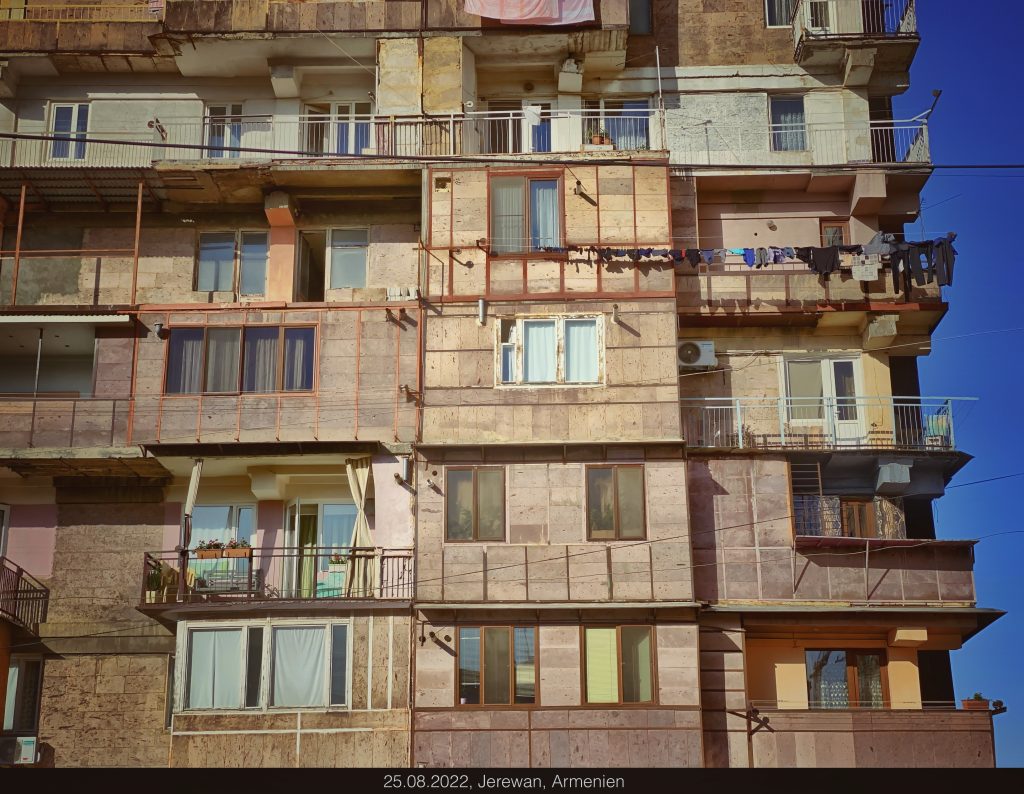

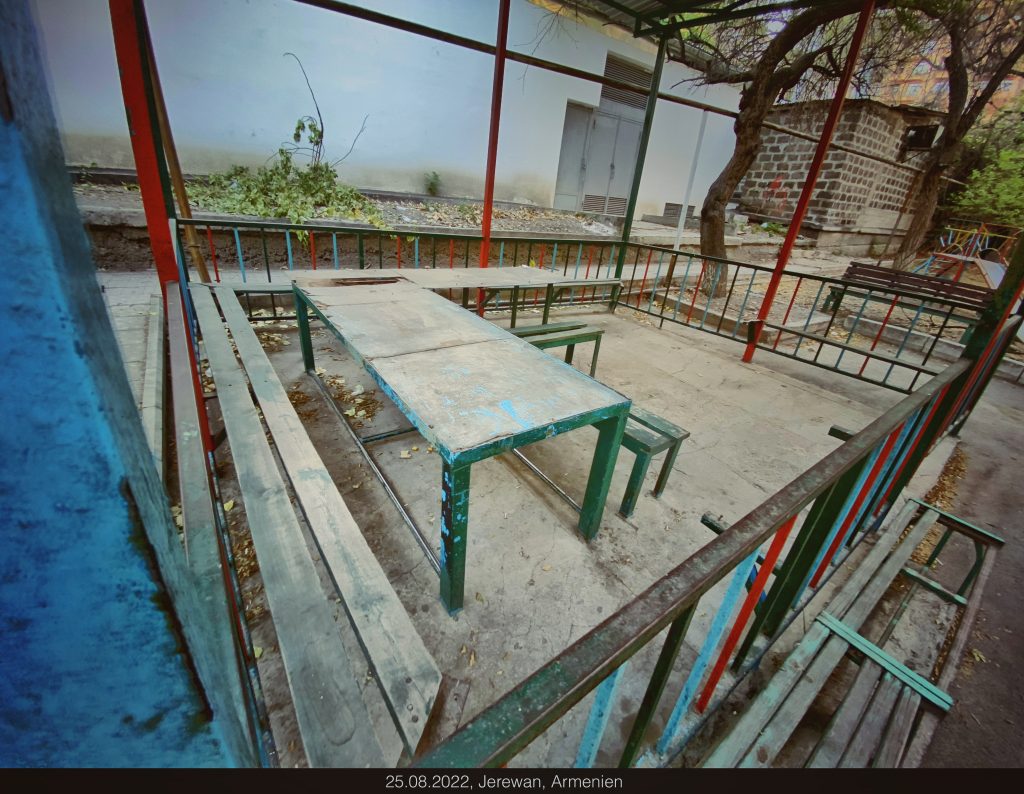

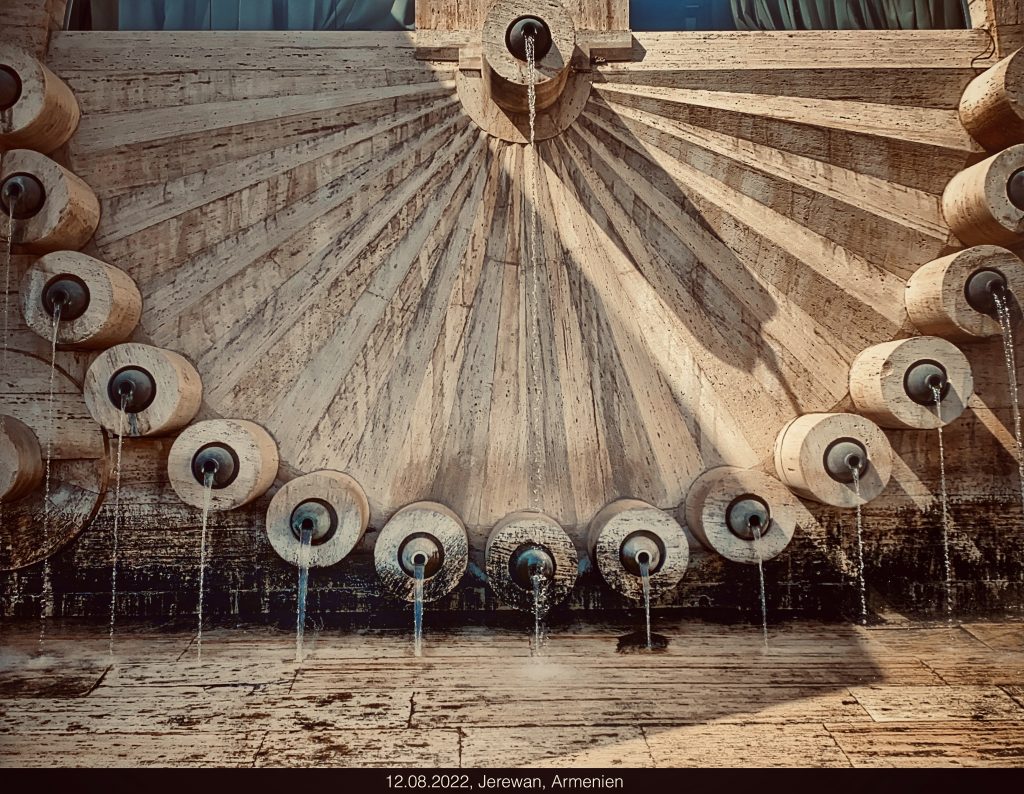

Yes, these are mighty buildings. These blocks of rust-red and orange-coloured tuff stones and tiles were the way out of the slums for many people when they were built. We walk through narrow corridors between cool houses. The corridors overgrown with vines and its foliage, rose bushes at the corners and other green plants and trees bringing cooling temperatures to the city. Playgrounds and covered seating areas with drinking fountains in every courtyard. Many houses were destroyed by earthquakes in the 70th and 80th, the remains cleared away and replaced by theses apartment blocks.

Even though many buildings in the Yerevan district of Arabkir look frightening at first glance. Brutalist cube architecture, piled up to five to ten storeys, clad in pink tufa stone, inside the tenants and owners have designed their flats individually. Some have chiselled open walls, enlarged rooms at the expense of hallways, others have planted fire escapes. It all seems confusing, but it also shows freedom and space to develop.

“Artists’ building”

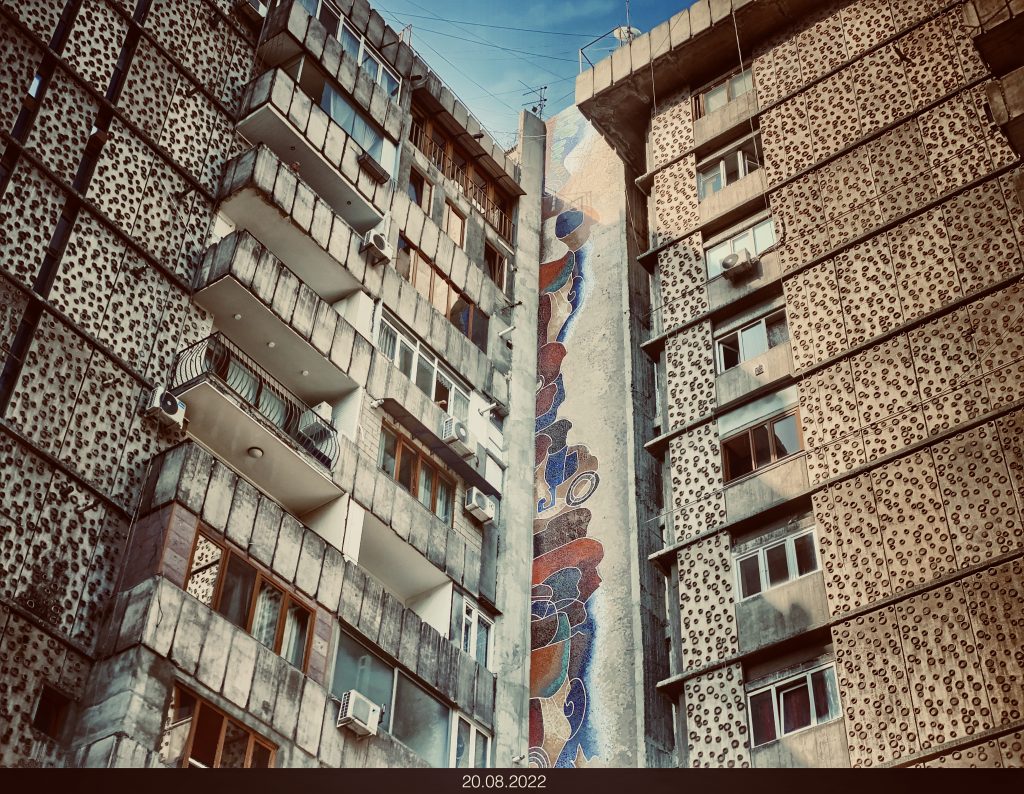

A very special building we found at 13 Hrachya Kochar St.

The Soviet Union had a habit of idealising certain professions that were considered “respectable” for the working proletariat. Engineers, architects, composers and academics were often honoured with murals, awards and even their own homes.

One such building is known as the “artists’ building”. This residential tower from the Brezhnev-era is easy to miss on Kochar Street. At first glance it looks like so many other nondescript prefabricated buildings from that era. However, a closer look reveals unique loft-style studios and flats that allow carpenters, sculptors and painters to practice their craft in a purpose-built space. These two-storey studios are all angled 45′ from the building structure to maximise views of Mount Ararat through their large windows.

While many of the artists still live there today with their studios, this old guard now shares the space with several architecture firms, creative agencies and tech start-ups.

Late Soviet modernism!

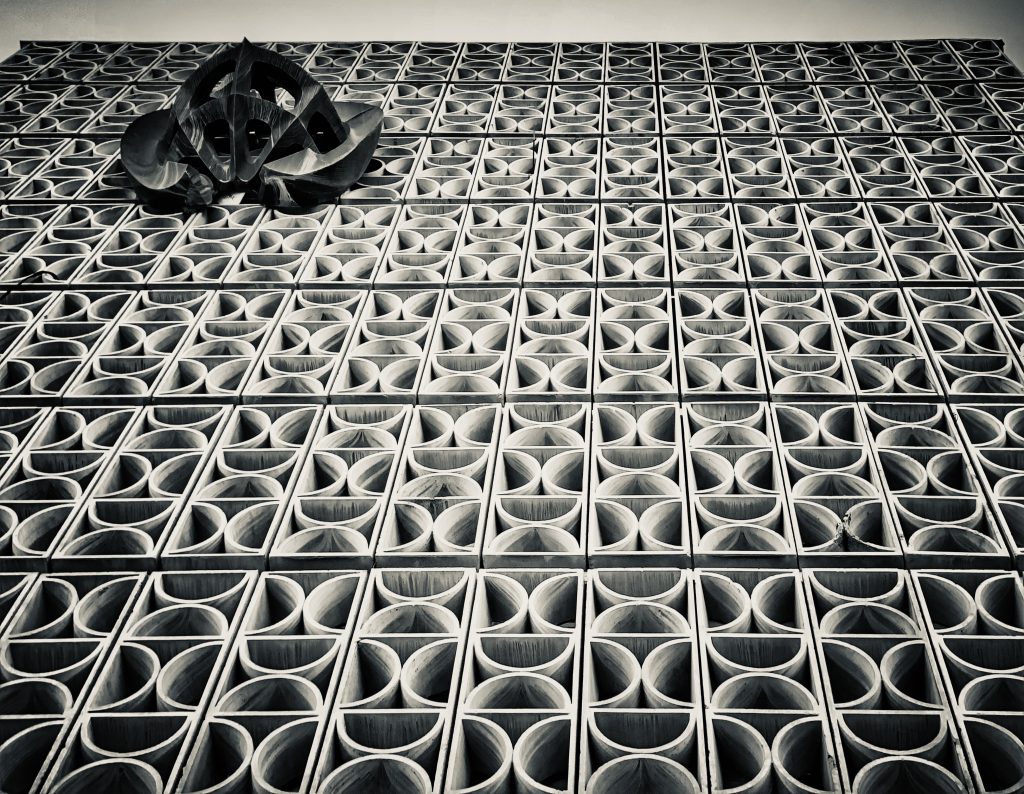

The Armenian capital is a kind of open-air museum of this era. Ornamentation that took over the standardised panels of the uniform apartment blocks. The “I-464” system, developed in 1958, allowed the construction of complete housing complexes from only 21 individual components. From the early 1960s, the I-464 was exported abroad, including to Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Mongolia and Cuba. In Yerevan, stylised flowers or lion heads can be discovered even on such standard buildings, referring to Armenia’s cultural heritage.

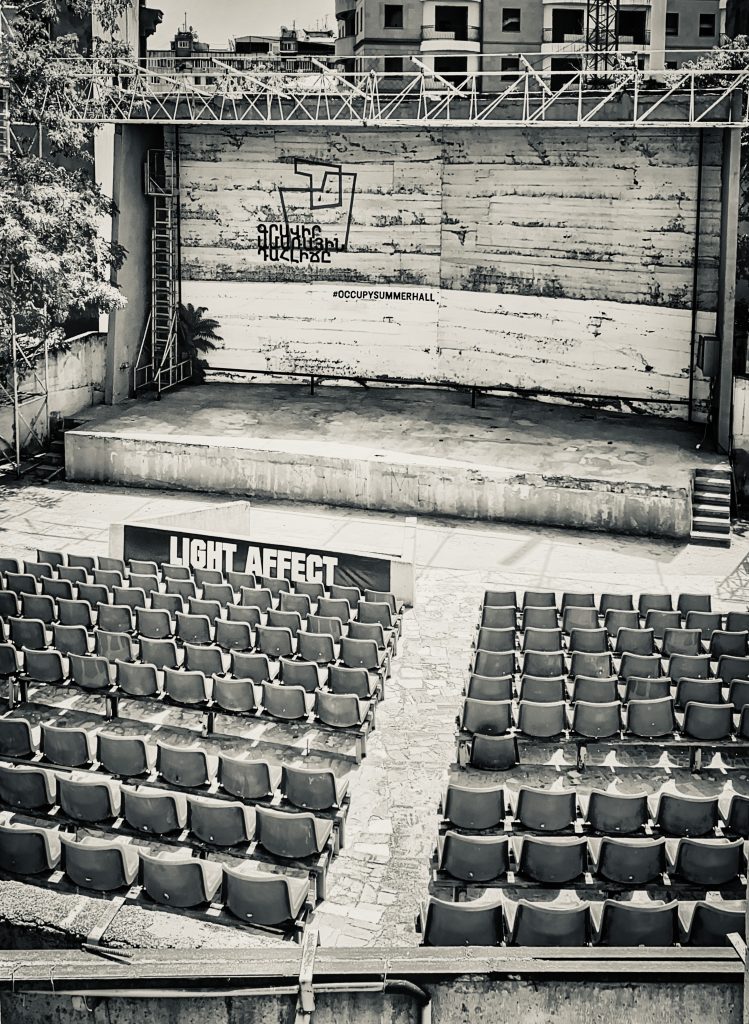

Concrete is crumbling, tiles are falling, window frames are rotting, staircases and terraces are cracked and have long since been closed off. Unfortunately, this also applies to the entire phenomenal “Rossija” cinema from 1975 with its two projection halls cantilevering like bird’s wings over a busy square.

The new use is disfiguring the building; sales kiosks of some kind are nesting in the cracks and open spaces.

The problem is often not the buildings themselves but rather their architectural alteration and use or abandonment and the resulting neglect by the residents and owners.

Architecture is exciting and tells history and stories when viewed in the context of them and its historical significance.

Once again serving the cliché with a joke from the non-existent Radio Yerevan:

Question to Radio Yerevan: What is capitalism?

Answer from Radio Yerevan: The exploitation of man by man.

Additional question: And what is communism?

Answer from Radio Yerevan: It’s the other way round.

Some more about my thoughts to architecture “My window to the world”

And my favourite picture exploring Yerevan: